1830s-40s menswear suit project -- part 3: Waistcoat

- clockworkfaerie

- Jan 12

- 25 min read

Previously Published in Foundations Revealed in 2020, no longer a functioning website.

Hello! Thank you for reading today. If you would like to support this and ongoing educational material on making historical clothing, please donate here: paypal.me/clockworkfaerie

This week, we're continuing on our journey of using a draft from a tailor's manual published in 1840, to make a full 3-piece suit of clothes.

On to the waistcoat! Here's some inspirational antiques to show what we're aiming for.

For the waistcoat and frock coat drafts, we’ll need to follow the directions on the cover page and make a set of proportional scales. Don’t worry, it’s pretty painless and I’ll walk you through it.

First, let’s take a few measurements.

I am an Assigned Female At Birth person but this draft is useable for anyone! I will talk through any points that may need extra care in measuring, which might differ between the sexes.

We only need 6 measurements for the waistcoat. The first two will be familiar but after that they get a little tricky so I’ve made a video to show you how I measured.

1. -Chest/bust circumference, over shirt and any undergarments, as usual

1a. -Waist circumference

2. -From bone at base of neck, by line A, to the center front where you want the waistcoat lower edge

3.- From bone at base of neck, by line B, around front and straight down to waistcoat lower edge at side/side front

4. -From point 2 at center back up and over the top of the shoulder, under the arm, and back to point 2

5. -from point 1 at base of neck center back, around to front of shoulder as before, under the arm, and back to point 1

The first proportional scale is built on the last measurement there, number 5. The book’s directions are as follows:

“Should the measure from 1 around the front and bottom of scye and back to 1, be 26 [inches], 13 inches would be the one-half. This half is divided into halves, fourths, eights, sixteenths, and thirty-seconds. It should again be divided into thirds, sixths, twelfths, and twenty-fourths.”

Also: “The scale divided from the measure taken from 1 to 1 will be used to obtain the distance directed by every sentence that is marked thus *, and the scale divided from the measure taken from 2 to 2 will be used to obtain all distances not marked as above.”

So, we also need to make a little divided paper strip from measurement 4 in the list up there, point 2 to 2. For me that measurement was 27.5”. I cut a length of paper 13.75” as instructed, then proceed to fold it in half and mark, fold it into thirds and mark, and fold and mark the smaller divisions of each fraction. Mine looks like this:

If you are drafting digitally, you simply need to make a rectangle in the right length and mark it out with some fraction math to help you do the draft. For this draft though, I do recommend working in paper. This is all about drawing intuitive, beautiful shapes to proportion.

Here are the measurements I’m using for the draft, in case you want to follow along:

36.5” bust/chest

30” waist

27” front length (to center waist plus length past that point)

23.5” length at side front

Point 2-2: 27”

Point 1-1: 26”

I followed their instructions which say to split the bust evenly into quarters for this draft. This worked well for me, however I’m of very average bust size and am wearing a slightly compressive bralette under my linen shirt. If you are very busty it may be better to measure Front bust and Back bust separately so as to place the side seam correctly and avoid making the front armhole too far forward.

Ok! We’re all measured, got our proportional scales made. Let’s jump into the draft!

Here’s the book’s illustration of what we’re aiming for.

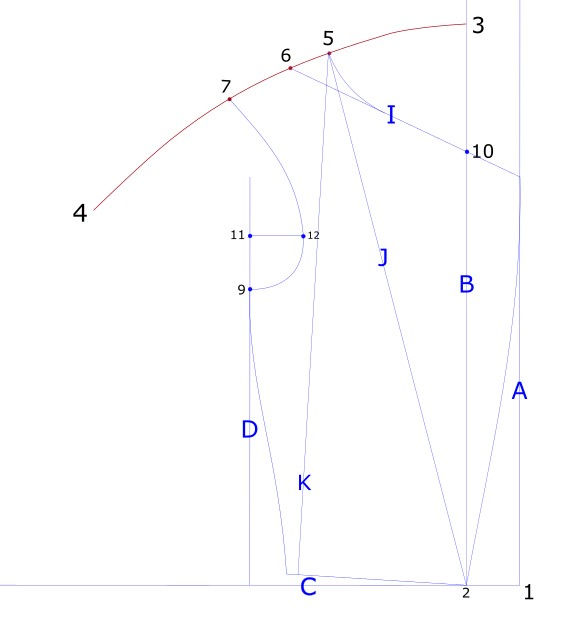

We start with a long line down the right side, an inch or two from the edge of the paper. This is line A, and represents the edge of the cloth.

Next, we square a line near the bottom (again a bit from the edge of the paper) out to the left, as a guide for the bottom-most edge of the draft. This is line C.

Point 1 is in the corner. The directions start,

“From 1 to 2 is 1-6.”

This sentence does not end with a *, so we use the scale we made from the “point 2-2” measurement and measure out one sixth, from point 1 to point 2 on our draft. (For me it’s about 2.25”.)

Square a line up from your new point 2, and label it B.

Next, we have: “From 2, sweep 3 and 4 by length of forepart, which is usually 1-6 less than the measure for the length.” This is your “front length” measurement, minus what will be half of the back neck. If you read ahead a bit we find on the draft for the back neck that they use ¼ on the 2-2 scale ruler, so rather than using 1/6 (which will be very small), I used the 1/4 measurement instead. So my back neck is 3.375”, instead of 2.25”. Either of these will work but we need to pick ONE and be consistent.

So, mark the front length minus either 1/6 or 1/4 on line B. Use a string or a long ruler to make an arc out past where a shoulder tip would end. Don’t worry about where it ends, as it’s not important. It’s a reference for the shoulder height.

“From line B to line D is 1/4 breast measure.” This is where you may want to instead use half of a front bust measurement if you split them up separately. Measure left the amount of ¼ breast measure from point 2 on line C, and square a new line upwards. Label it D.

Now we will mark a few points along the shoulder arc. “From [point] 3 to 5 is 1/3 and 1/12. From 5 to 7 is 1/3. From 5 to 6 is 1/8. From 3 to 10 is 1/3 and 1/12.*

For those which have two fractions of your scale, simply add the lengths together. Note that the last one there [point 3 to point 10] uses the other scale, the * marked one.

Note that although line D goes right through point 7 in the book’s illustration, it may not on our draft.

We continue marking points to outline the armscye.

“From 7 to 11 is 1/3 and 1/12. Square with line D, draw line from 11 to 12. From 11 to 12 is 1/6. From 11 to 9 is 1/6.”

Next: “Apply measure from the top of back to 8, as represented by line K. Form scye and neck-gorge, apply ¼ waist measure from 2 to 8, adding seam and turn-in. Form side-seam, bottom, and breast, and you are ready to cut.”

Ok so for line K: using a regular tape measure, take the side-front length, take away the half back-neck measurement from it, and draw it from point 5 straight down to a vague side-front waist. This is just to help you put the tilt of the waist hem at the right angle. While you’re at it, we can set up line J from point 5 to point 2 just to double check the front length and help us draw the neck. If it’s too short or long, adjust the length at point 2 before continuing.

Draw a line from 6 straight through 10, touching line A. This is to help set up the gorge line at the neck. Draw a curve from 5 down to meet line I to make the side of the neck opening. Draw a curve from point 2 up to meet the point where lines A and I meet. This is your center front and lower lapel.

For the waist, draw a smooth curve from point 2 out to meet the end of line K and going past it, making this line as long as ¼ the waist measurement. I didn’t add any extra for seams because I like to add the seam allowance after the pieces are all drafted, and that worked fine here since I drafted on paper and made a paper copy. If you’re chalking directly onto the fabric, leave yourself a bit of room for seam allowances.

After the waist is established, draw the side seam with a smooth curve up to point 9. Draw the armscye from 9 to 12 to 7. Feel free to use French curves if you have them, but otherwise just try to copy the general shape.

All right! We have the front waistcoat shape! It’s all set up to become a notched lapel, single-breasted waistcoat. I want a shawl collar though so I’m going to re-shape the front a bit after I do the back waistcoat draft.

“Draw line E. From 9 to width of back at line F is ¼ breast measure, and 2 seams.”

Square a line from D at point 9, going left. Mark 1/4 of the breast measurement (or half the back bust if you’re using that instead). This will be the center back. Square line E up and down from it.

“From F to G is ½.* From G to H is ¼.* Length of line H is ¼. Length of line G is ½. Form shoulder seam and scye. From line E to 13 is ¼ waist measure, allowing seams. Form side seam of back, by side-seam of fore-part, and you are ready to cut. “

Note that the first two are height markers, and use the * ruler. The next two instructions (lengths of horizontal lines) use the other scale ruler.

Here’s the lines for the upper back marked out. We use line G to mark the edge of the outer shoulder corner, and H to mark the general vicinity of the back neck corner. Check the length of the shoulder with the front once it’s drawn to make sure they’ll match. It’s nice to make the back shoulder a little longer (1/4” or so) than the front and ease it in to curve over the back of the shoulder, but it’s not essential. I chose to draw this extra length on the neck edge to help shape the neck a bit instead of having just a straight line across at H.

Shape the back armscye in the same manner as for the front. It’s ok if this is cut too big. Make nice squared corners at the shoulder and side seams so as to make a smooth edge.

For the bottom waist edge, square a line from E that touches the corner of your waist/side seam on the waistcoat front. Mark the ¼ waist measurement on this line (point 13), and draw a side seam from 13 up to 9, matching the front curve as much as possible.

The shapes are there! I’ve outlined them in black so you can see the final shape a bit better. Let’s come back to that front piece and do the shawl collar now that we have the back neck curve established.

The top drawing in the original book gives the general shape for a few different collar types, all overlapped. We can see a typical notch collar with a roll (like a suit jacket), a regency-style stand collar with slight cutaway front, and the shawl collar in thin dotted line.

If the directions I give here are too vague, feel free to use a modern patternmaking book to apply a collar (suggested title below in Bibliography) in a more precise manner.

Shawl Collar

On the front piece, extend the neck curve in a straight line the amount of the back neck. (3.375” in my case.)

There’s no formula for where to put the break point. Pick a spot on the center front where you would like the collar to start (e.g. the height of the front opening) and go for it. The illustration has the center front extended a bit to meet the point. This is building in space for the buttonhole overlap, so don’t make it more than ¾” or so wide past the center front line.

I chose a point roughly equivalent to the illustration (mid-bust to underbust area on me) because a longer collar helps give the illusion of more torso length, which I need as a long-legged but short torso-ed person. Draw a line from 2 up to where you want the front edge to stop and the collar to start.

Draw a straight line from this break point up to 1” or 1.5” above where the neck extension is if you were to square a line out from the neck extension.

Draw a curve for the shawl collar. Copy the illustration or my drawing, and just aim for the general shape. We’ll firm up the back neck in a bit—for now just put it in that general area, aiming for a back collar width of between 3 to 5 inches.

For the back neck of the collar: Square a line from your collar edge (red line) to where the neck extension ends (black line). This will likely mean that it’s not square at that edge. This is fine. You can also curve the center back collar line to more smoothly connect the two and make both corners square. Err on the side of too long an outer edge for the collar. It’s easy to pin out excess in a toile fitting, but harder to see what’s going on if it’s too short.

Alrighty! The waistcoat is drafted! Let’s make a toile and check the fit. I put button markings on ½” from the edge and that worked well for me. As mentioned earlier, the farther you draw the break point to the right, the more it will need to overlap (or be padded out) in that area.

Waistcoat Toile Fitting

Hey, not bad! I’m pretty pleased with how this draft turned out! We have a beautiful dropped shoulder, the collar shape is nice, and I love the pointed waist so much. I do need to open the high hip up a bit, and take in some excess at the side seams above the waist. (I was a bit ambitious with that side seam curve, it looked like a corset seam!)

I am taking some width out of only the middle center back, which means that it’s now a curved line and I can’t cut it on the fold anymore, it has to be a seam. This is fine with me, as all of the extant garments I’m finding photos of have a center back seam.

The collar break point is drooping a little. It goes away when I tug the waistcoat down, and I do notice that it’s more prominent on one side than the other. I tried pinching it out in a dart but immediately hated the shape that made, it’s far too flat. I also tried padding the chest out a few different ways and played with the shoulder but that wasn’t quite the right shape either. Overlapping the center fronts more does help, so I think I’ll bring that overlap in more for the final one.

At this point I wish to mention that in Norah Waugh’s book “The Cut of Men’s Clothes”, there is an original waistcoat pattern from 1840 which has darts extending into the arm and the collar area! So, if you find yourself needing a dart here or there, you are allowed! It seems that they were avoiding the dart coming up from the hem.

Now that we have a shape we like, I’ll show you how to make all the little pattern pieces for the various bits we’ll need.

I’m making this waistcoat in lavender dotted silk taffeta for the outer layer. I’ll also need canvas for the inside front, lining for the inside, and plain cotton or linen for the back if my silk isn’t large enough to also cut the back. I do want functional pockets (pocket watch has to go somewhere!), so I’ll need pocketing as well.

In addition to tracing off the two large pieces we’ve just made and adding seam allowances, we’ll also need a facing piece for the fronts, welt pocket pieces, optional welt pocket bags, and optional back buckle pieces. You can leave off any back waist adjustment completely if you’re confident in the fit, there are period examples like that. You may also choose to do a little tie in the back instead of a buckle.

Here’s a few examples.

Earlier Buckle back: https://www.etsy.com/listing/574351689/gents-black-silk-waistcoat-circa-1840s?show_sold_out_detail=1&ref=nla_listing_details

Tie adjustment in the back. Plus delightful needlepoint foxes on the front. http://www.extantgowns.com/2015/05/1840s-mens-embroidered-waistcoat.html

Whatever you choose, I do notice that the back adjustments are usually put right on the back piece and not included in the side seam, the way they are for later waistcoats.

Patternmaking Final Pieces

I’m going to make paper pieces for everything, and make small adjustments on the paper pieces rather than trying to remember to scoot them tiny amounts as I’m sewing. I’ll show you as we go.

I’m going to add a fish-shaped dart underneath the shawl collar. I don’t honestly know if my ancestors did this or not for shawl collars, but I find it super helpful in modern waistcoats, in keeping a nice rolled shape. This dart will NOT be on the facing piece, only the waistcoat front piece that rolls underneath it. It’s 4” long and only ¼” wide at the center.

For the front, draw a line up through the middle of the piece: starting about 2 to 3” away from the bottom center front point, then extend up through the middle of the shoulder. The area from this line to the right will be the front facing. From this line to the left will be the front lining.

Notice how the red line at the front edge (the facing piece’s outline) goes OUT about 1/8” on the collar, and IN about 1/8” on the body? That is to help the collar roll in the right direction, and to help the button area hold a nice curve around the body and keep the seam from being seen. You can do this on the pattern, or just scoot those pieces in and out as you’re sewing (or cutting!).

We can also make a back facing. It’s not necessary, but it does help keep the back collar from falling onto the neck. Mark where your front facing edge is on the shoulder, and transfer to the back so that the facing seams will meet. Draw a parallel line to the back neck out from the center back to meet it.

For the front lining piece, the two 20th century tailoring manuals I have both say to make the lining a tad bit bigger than the outer. This is to make sure the lining isn’t too small and avoids it pulling the outer pieces out of shape. The earlier one (Practical Tailoring) says to add a little pleat in the shoulder. The later one (Classic Tailoring Techniques) says to add a pleat going across the middle of the piece. I’m going to move the armhole corner point of my lining piece up and out ¼”, like this:

When sewing, still sew the armholes together as usual, and the extra seam length will be eased in, but the body will now be a little bit wider than the outer layer. Perfect! This is also something you could simply do by scooting the pieces apart while sewing, or marking the corner point and armscye when cutting, moving the piece away ¼”, and connecting the lines.

For the canvas pieces, we trace it like so.

Practical Tailoring has you cut only a section of the front in canvas, and Classic Tailoring Techniques has you cut the entire front in fusible interfacing. Either way, the front “canvas” piece must be cut on the bias.

There is also a small canvas piece for the back neck. I made mine about 3” wide. Cut it on the fold if at all possible to avoid bulk at the center back seam.

These pieces should be cut with NO seam allowances if you’re using canvas.

Let’s add some fun details. Buttons and welt pockets!

Two welt pockets seem very standard. I notice they tend to be higher on the body than the 1920s vests we’re used to seeing, and also they aren’t slanted to be parallel with the waist hem, but instead seem to be more parallel with the floor. I see both squared and angled welts, but squared is more common. You can go CRAZY with pockets, I’ve read about some on the INSIDE of the waistcoats even, or special eyeglasses pockets made with chamois leather (don’t iron over those). Pockets=time=money.

A breast pocket or two, also welted or piped, is often seen. I don’t like how it hits on my bust so I’m not including one, but feel free to add one yourself.

I trace a line for the bottom of the lower welt pocket on my main pattern, and add two parallel lines ¼” and ½” above it to make the pocket opening. I also make a rectangle piece 1.25” finished width for the pocket welt itself. Last, I draw a pocket bag that will attach to the top edge of my pocket opening and isn’t too long/won’t get caught up in the waist hem.

I’m not making a separate back lining, I’ll just use the top piece. I’m also not making a buckle strap piece, I’ll just cut a sloped rectangle to a generally correct size out of the scraps once I’ve already cut the larger pieces.

Construction

I’ll be using a mix of modern sewing and older style tailoring methods to make this waistcoat, with an eye to the shape and look of the museum waistcoats. Some of the shaping techniques one does with a wool waistcoat just don’t work as well in silk, or a shawl collar. Since I am in fact making a silk waistcoat with a shawl collar, I’ll leave those techniques for another time.

I’m using the cotton basting thread from wawak.com for all my basting. It’s lovely stuff and doesn’t leave marks when you iron. You may use something similar or a lightweight silk thread to avoid ironed in thread marks on the surface of your fabric.

First step is to cut the pieces. Don’t mark anything like darts or pockets yet, because the front canvas needs to be applied before we do those marks.

I’m using a lightweight linen buckram for my “canvas” pieces, and some light wool flannel on the underside of the facing piece to keep any seam allowances from showing through. Cut the front canvas on the bias, but cut the back neck canvas piece on the straight.

Sew up the center back seam of the back pieces if needed. I cut my back from the same fabric as the front because I had enough and didn’t want it to languish in a closet, but feel free to cut your waistcoat back out of plain white or natural colored cotton or linen.

Baste the canvas pieces to the inside of the back piece and the front pieces by stitching close to the edge with LARGE running stitches. The back canvas piece does go up into the shoulder and neck seam allowance. The front canvas pieces should have no seam allowance on the front and lower edges, but they should have seam allowance going into the shoulder and neck. If you want to be super precise you can cut the canvas WITH seam allowance and lay it on the main fabric which has had its seamlines thread-marked. Fold it over on the seamlines, and cut the canvas where the crease is.

If your pocket goes off the edge of the canvas as mine does, baste a scrap canvas extension from the side seam to overlap the canvas edge by ¼” or so. You can do this with upper pockets into the armhole as well. It helps keep the pocket opening from pulling out of shape or stretching as you're sewing it.

Mark the pocket openings, neck dart, and roll line on the canvas with pencil or chalk. Thread-mark the pocket flap opening so that it can be seen from the right side. Mark the collar roll line and collar dart on the front canvas piece, so that you can see it from the wrong side.

Time to make the pockets! Pockets are easily the most time-consuming part of a waistcoat. I chose two lower pockets as I didn’t like how the upper ones were hitting my bust, but one upper pocket seems like the norm for this time in fashion.

I cut my welts as a single piece to fold over at the top. Sew across the short ends, clip as needed, and turn. I also cut a little rectangle of wool flannel to put inside my pocket welts to help bulk it up a little, and basted it in.

Now that the welt is done, we apply it to the waistcoat front. Put it folded edge pointing down, so that the ¼” seam allowance touches the middle line of the marked pocket triple line. Sew it along the bottom line with a SMALL stitch length, and stop 1mm or so from the edge of the welt.

Now we add the pocket bag pieces. Place one at the upper part of the pocket so that the raw edge is touching the welt’s raw edge, and sew it down ¼” away (along the top of the triple pocket line), making sure you stop the ends at a place that will be hidden by the welt once it’s turned up. Place the other pocket bag piece right over the welt, and sew 1mm inside the existing seam.

The exciting part! Now we cut the pocket open! Cut only the front piece (not the pocket bags or welt) like so.

You can now turn the pocket bags to the inside of the waistcoat, and make sure the welt is pointing up and covering the pocket opening. Turn the little side triangles to the inside of the waistcoat. Press as needed to flatten these seams. (If you’re using silk, like me, press with a thin cotton or flannel press cloth so that you don’t scorch any raised weave fabrics (like satin or figured weaves) or flatten it too much.)

Flip up the front of the waistcoat so that it’s out of the way and machine stitch those little side triangles down to the pocket bags beneath them, as close to the pocket opening as possible. Continue down and around the pocket bag to sew it closed. Do watch the length of the pocket bag, so that it doesn’t get caught in the bottom hem seam.

Stitch down the edges of the pocket welt. You can do a single line, or a box as I have done here.

Stitch the neck dart, if using. I haven’t been able to see if museum waistcoats are using this little detail or not, but I like it because it helps the collar roll correctly without having to padstitch the entire shawl collar. My dart is 4” long and ¼” wide at the center, tapering to 0” at the ends. I placed it at a spot about even with the hollow between bust and collarbone, where the collar is most likely to be pushed back out.

Next, we turn to the facings and linings.

I basted some thin wool flannel to the inside of my front facing pieces to help pad them out and avoid a visible seam allowance line once sewn, turned, and pressed. You definitely don’t have to do this step, I just wanted to bulk it up a bit as the silk taffeta was quite thin. Once any extra material is basted on, proceed to sew the front facing to the front lining piece.

If you want to make a pocket in the front lining/facing, this is the time to do it. Jetted or piped pockets are the usual style, but flap or welt pockets can work too. They’re constructed the same for an inside pocket as they would be for an outer pocket. Watch that your pocket doesn’t creep into the roll line area if it’s higher on the chest. For people with breasts it’s more comfortable to put this pocket below the bust, along the side-front of the ribs.

If you made a back neck facing (optional), now is the time to attach it to the back lining.

Time to sew the shoulders together! After that’s done, sew the center back seam of the collars to each other, press open. Clip the inside corner on the front shawl-collar pieces, and sew the neck of the collar to the neck of the body. Do the same process for the lining pieces and the outer layer pieces.

Now you’ll have two pieces that look like this: an outer layer, and a lining layer. The side seams are NOT sewn yet.

Lay the two layers over each other, right sides together, and sew them together along all the edges EXCEPT the side seams. I usually do the back hem first, them the long front seam that goes from one side seam, to center front, up and around the neck, to the other side seam. Then do the armholes last.

Clip any curves and corners as needed before we turn this right side out. I usually trim sharp corners, and clip and trim the armhole like this:

Now the fun part! For each side separately: reach your arm up inside through a back side seam opening, all the way through the shoulder to the front. Grab the center front bottom corner of the front, and turn the whole piece inside out so it looks like this.

Time for a mega pressing session! Press all of the edges, being sure to note that point on the front where it changes from buttons to collar, and rolling the facing to the outside of the seam above the roll point on center front, and rolling the facing to the inside in the button area. I also roll the lining slightly to the inside at the armholes. The side seam is still not sewn at this point, we’ll do that next.

For the side seam: grab the outer layers (left front and left back, for example) and start pinning them together. Do you see how if you kept going onto the lining, the seam would be a loop? Sew as much of this loop as you can, leaving a small access gap in the lining. We’ll hand-stitch the gap closed afterwards, using a felling stitch and not catching the outer layer. Before you close it up entirely, get in there and press the seam allowance towards the back. You may need to re-press the hem or armhole as well.

A small but helpful detail: poke a pin through the center back neck, where the collar seam meets the neck seam, from lining to outer layer, to match the two neck seams up evenly. “Stitch in the ditch” (stitch right in the seam so that it can’t be seen from the outside) for an inch or so with a machine at this point to keep the collar all together.

For the back belt:

I’m using these images of an antique c 1840s waistcoat as my inspiration.

I’m making a tapered rectangle that will be a turned tube with finished ends. I measure my belt buckle to see what strap width will fit (turns out ¾” is about right) and make a 2” long segment at the narrower end of my strips that is that width. I started out making each strap the same width as the back piece but they didn’t even need that much—I ended up cutting off about 2”.

Here are the pieces pinned onto the back after they’ve been stitched, turned through the large end, and pressed. Buckles are all different so I won’t bore you with how to attach them, but mine I simply folded through the end bar and machine stitched through all the belt layers to secure on that side. I also pressed a crease into the wide end, turned all the edges inward, and pinned in place for the next step—stitching the belt through all the waistcoat layers onto the back. You can see those stitch lines here in the grey thread. A box is the usual pattern. It may be narrow or wide.

We are so close! Only buttons and buttonholes left to go!

I decided to do as small a covered button as possible for this waistcoat, as that’s what I saw on the museum/extant waistcoats I looked at. After trying both a regular modern flat covered button and a more domed version to try and get the shape I saw in extant waistcoats, I decided on the domed ones so that’s what I’ll show you here. You can definitely make your own buttons using a bone or wooden button mold or a brass ring and thread to make the shank, but I decided to incorporate modern metal button blanks with metal shanks so as to avoid excess wear and tear on the buttons.

Start with regular covered button blanks. I’ve got the kind with a metal shank attached and little teeth to hold the fabric. I’m using 3/8” diameter, they have a tiny bit of dome to them but not very much.

Cut two circles of fabric, one silk and one cotton (to avoid the silk rubbing directly on the metal). We also need something to stuff the dome with. I tried polyfill and a little bit of cotton quilt batting, the latter was my favorite. Of that, I cut a strip about 3/8” x 1 ¼” and rolled it up into a cylinder and squished it flat with my fingers, like a knish or a cinnamon roll. Whatever you use, it needs to be pretty solid and squish-resistant because these buttons will be under quite a bit of strain when you go to button them.

Knot a thread and hand-sew a little gathering/running stitch around the edge of your circle (for me it was 1/8” from the edge). Put you bit of stuffing in the center of the circle, the button blank on top of that, and gather it up around the whole package. Pull it tight! Press the excess fabric in the middle down into the center of the button blank as much as you can. Secure everything with stitches back and forth across and around the underside of the button around the shank. Make a few extra for future repairs and put them in a pocket.

I decided on machine-made buttonholes for this project, as I wanted a really thin buttonhole and didn’t trust my hand-buttonhole skills to pull it off. Check my trousers or shirt article in this same series for hand buttonhole instructions if you would like to make yours by hand!

I made a few test buttonholes to check that they were the right size for the button and to see if changing the stitch width on my machine made a narrower buttonhole (yes it did, the left buttonhole here is what I’ll be using).

Time to mark those buttonholes! Get out your pattern if needed. I marked the top buttonhole about 5/8” down from the roll point, and the last buttonhole at the bottom about even with the waist. I marked the top buttonhole about ½” in from the edge, and the lower one about 1/4”-3/8” in from the edge, since that’s what I had done on the toile. Mark your top and bottom buttonholes, draw a straight line between them, then divide that length by one less than the number of buttons (divide by 3 for a 4-button waistcoat, for example) to get the measurement between buttons. I suggest no more than 2 inches between buttons.

I see anything from 4 to 7 buttons on extant waistcoats, do what makes you happy! I went with 4 here since it’s a longer collar/lower neck opening. 7 would be appropriate for the waistcoats that button up much higher.

The lower edge below the buttons is left open to split a bit. This is purely a stylistic choice—some waistcoats of this time are cut almost straight across from the waist, some have a bit of point, some have a lot of point. Whatever the case, it should still be straight across or a single point when worn, not a little W shape—that comes later on in the Victorian era. Many of the museum waistcoats laid flat look as if they have that shape, but that’s because of the way they’re cut curved over the belly—when worn, those points would meet and form a single one.

At this point, go ahead and remove all those pesky basting threads! Do a final (gentle) press to remove any basting thread dimples or neaten up areas that got creased during the sewing. Steam is your friend.

I did NOT prick-stitch the edge of my silk waistcoat this time.

If you really want an ultra-flat edge, you can prick-stitch any of the edges you wish. It is most common to see it on the front edge (usually ending where the facing ends on the hem, somewhere below the pocket) and the armholes. I show this stitch in the Trouser article of this series, during the pocket flap and waistband edge finishing.

This is not a time to use a fancy contrasting thread color, that’s a modern detail. Pick a nice silk thread in a matching color and make the stitches as invisible as possible, through all layers, anywhere from 1/8” to ½” from the edge depending on your fabric, seam allowance, and thread. I generally go for a narrower prick-stitch, close to the edge, through all the seam allowances.

Final Photos

I’m super pleased with how this turned out! The silhouette and lines are really coming together, and I am falling even more in love with this era.

Things I might do differently if I did it all again:

I’d choose a heftier fabric for my main fabric. This taffeta-weight stuff is lovely but all the wrinkles show and I see why so many of the extant waistcoats I’m seeing are these heavy satins or amazing voided velvet brocades. A heavier fabric will really make this an easier sew!

I love the fit—the collar is lovely and the waist point is lovely and I’m happy with the amount of tightness and ease in the waist and bust. The only thing I might change as far as the pattern cut is to cut in the top of the shoulder about ¾”. This is an issue I also had with the frock-coat pattern (more on that to come), and it’s an alteration we always had to make at Denver Bespoke when starting with a men’s pattern or men’s suit jacket, when I worked there and we made lots of menswear for women's bodies. Since the chest is drafted to my bust size, there’s no change needed at the underarm, just the top of the shoulder. A waistcoat can be cut a little farther in on the shoulder anyway, it doesn’t need to sit right at the edge.

I had a lot of fun making this, and I hope you do too! Let me know how the draft works out for you, and don’t hesitate to ask questions if you get stuck. I’ll see you soon for the frock coat!

Bibliography:

Practical Tailoring by J.E. Liberty. 1933

The Tailors’ Master-Piece By Scott and Wilson. 1840

Classic Tailoring Techniques by Roberto Cabrera and Patricia Flaherty-Meyers, 1st ed.1983

Patternmaking for Fashion Design by Helen Joseph-Armstrong, 2nd ed. 1995 (This is a school textbook so it's had many new editions since then, but there's still lots of good information in the older editions.)

Comments